As far back as he can remember, Rufus Parnell Jones has always felt the need for speed. “You know how when you pull up to a stop sign, you have the instinct to be first? I just took that to another level,” he says.

His first taste came in the mid-1940s as a youth in Torrance. At age 11, he started his first job breaking quarter horses. Torrance was still part of the Wild West, consisting of miles of prairie, farmland and dairies.

He saved enough money to buy his own horse and began riding in amateur races in Carson. By 13, he had grown too tall to be a jockey, so he traded his horse in for a hotrod.

“I had a track roadster 23 T-Bucket with a (Ford) Model A engine and no fenders on it. I was always getting caught speeding down the hill on PCH,” he says. “All of the cops in Torrance and Redondo knew me. We would take off across the flower fields to get away.”

At 17, under the name Parnelli Jones, he entered his first professional race—a jalopy race at Carrell Speedway in Gardena. Childhood friend Billy Calder had given him the nickname “Parnelli,” hoping the Jones family would not discover their son was racing cars as a minor.

From there he quickly developed his skills, racing in many different classes in the 1950s. “I was at an age where I could have easily turned in the wrong direction,” he says. “A lot of my friends went to jail. Racing helped keep me out of trouble.”

Jones’ first major championship was the Midwest Region Sprint Car Title in 1960. During that race, promoter J.C. Agajanian spotted his talent and became his sponsor.

He made his debut at Indianapolis in 1961. In his first Indy 500 race, he led early and ran among the leaders until being hit with engine problems and a flying stone from the track. The blow bloodied his face and blurred his vision. The combination slowed him to a 12th-place finish.

However, his skill didn’t go unnoticed. He was honored with the title “Indianapolis 500 Rookie of the Year,” along with Bobby Marshman.

In 1962, Jones became the first driver to qualify at the Indy 500 at over 150 mph. He repeated the feat in 1963 and dominated the race to win the 500 by a comfortable margin.

After his Indy 500 win, opinions back home in Torrance shifted about the former drag racer. City officials awarded him the key to the city at a special recognition dinner.

“Back in high school I had dated a girl, and her mother hated me because she thought I was trouble,” he says. “Her dad worked for the Torrance Parks and Recreation Department. When I saw him at the dinner, let’s just say I felt vindicated.”

In a span of seven years at Indy, Jones led a total of 492 laps—almost twice that of any other driver that period. He won six additional Indy car races. He also took the USAC Stock Car Championship title in 1964.

In 1967 at age 34, he attempted to win the 500 a third time. He led for the majority of the race, until the transmission bearing failed with just eight miles to go.

“I had the lap lead, when I starting thinking about how winning was not going to be as great as it had been the first time,” he says. “It was sad to lose, but later I was thinking, ‘If it’s not that great of a feeling to win, what am I doing it for?’”

Around that same time, Jones began testing Firestone racing tires at Indianapolis, where he became close friends with the Firestone family. He and long-time friend Vel Miletich decided to rent space at a Ford car dealership in Torrance and begin selling retail tires for Firestone Tire Company.

One day while working at Vel’s Ford, a petite blonde named Judy wandered into the dealership after she had crashed her car. While both deny it was “love at first sight,” Jones invited her to eat lunch at the dealership’s café.

“I didn’t like her very much at first,” Jones says. In spite of that, the two began to date and married the next year—his last year of racing Indy.

“My future looked like it was in the tire business. It was the year (1967) I decided to get married, quit smoking and quit open-cockpit racing. I changed my whole life.”

Miletich and Jones would eventually buy the dealership, renaming it Vel’s Ford. The tire business expanded to 47 retail Parnelli Jones Tire Centers in four states. In addition, he and Miletich founded Parnelli Jones Enterprises, a chain of Firestone Racing Tires, in 14 Western United States, along with Parnelli Jones Wholesale, a reseller that sold and distributed shock absorbers, passenger car tires and other automotive products to retail tire dealers.

After getting married, the Joneses moved to the Rolling Hills home where they still live today, making good on Parnelli’s promise to “never live east of Denver.” The birth of their sons, P.J. and Page, followed.

“I spent the rest of my years with him,” Judy says. To that Parnelli replies with a tongue-in cheek grin, “She took the best years of my life.” Judy continues, “Athletes are very focused, and he is not an easy cookie.”

Although the couple shares honest and good natured jabs, something clearly holds their 48-year marriage together. According to Judy, the simple secret is “having your own bathroom.”

After retiring from open cockpit racing, Jones devoted his versatile driving talent to closed cockpit races, winning the SCCA TransAm Series and the Pike Peak Hill Climb—a race to the summit of Pikes Peak in Colorado.

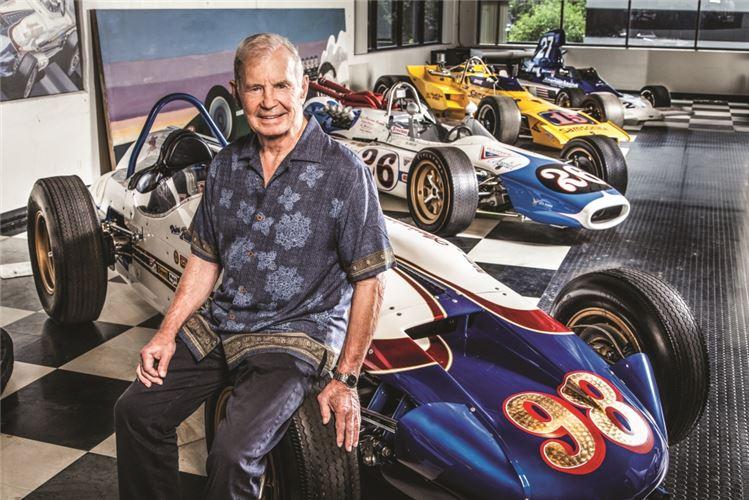

During his post-Indy years, Parnelli entered the ranks of “car entrant” with partner and longtime friend Miletich. The duo won 53 Indy races, including the 500 twice in 1970 and 1971, with a team composed of some the biggest names in racing history. These included Al Unser and Mario Andretti, who has referred to Jones as “the greatest driver of his era.” Today many of the beautifully preserved cars from the Vel/Parnelli collection are on permanent display at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Racing Capital of the World Hall of Fame Museum.

As parents, the Joneses recognized the dangers of racing. Despite their best efforts to steer their sons in a different direction, the apples fell close to the tree. With access to the best mentoring and equipment, sons P.J. and Page quickly became rising stars.

Page won 18 out of 42 of his races and was on the fast track to NASCAR. However, on September 25, 1994, fate took a dark turn. While leading a Sprint Car race at Ohio’s Eldora Speedway, his car flipped and was struck by another car.

“My first thought was that he couldn’t be hurt that bad,” Parnelli says. “But when I called the doctor and he said, ‘Mr. Jones, I think you’d better get here,’ it scared the hell out of me.”

Page sustained a broken shoulder, collarbone and serious head injury. He was airlifted to a nearby hospital where he spent three months in a coma.

“It brings tears to my eyes,” Parnelli says pondering the accident. “I was so fortunate. Racing is dangerous. You always kind of overlook it and say, ‘It won’t happen to me.’”

Page spent two years in hospitals and rehab, where he relearned basic skills such as walking and talking. Although today he still faces some motor skills challenges, he works alongside his dad at his Torrance office and co-parents his son and daughter with his wife, Jamie.

A close friend, Rich Sloan, captured much of Page’s recovery on video, which was recently included in a documentary called God Speed: The Story of Page Jones. Parnelli is working with the project’s producer, 1st Wave Productions, to promote the film—with the goal of increasing awareness about the challenges faced by those with traumatic brain injuries, including war veterans. Proceeds will go toward the Brain Injury Foundation and the Page Jones Fund Foundation, established to contribute to programs that assist those who sustain a brain injury and their families, with an emphasis on the importance of rehabilitation.

In addition to his work with Page’s foundation and racing appearances, at 82 Parnelli rolls into his office daily in North Torrance to manage real estate and other business holdings. “I show up just in time to go to lunch and then spend a few hours working,” he says. A visit to his office is like a trip to the Speedway Hall of Fame, with floor-to-ceiling prints of Parnelli with U.S. presidents, celebrities and racing’s most notable icons.

Page’s accident made the Joneses keenly aware of the importance of good health care and hospitals. This led to their support of City of Hope, Daniel Freeman Memorial Hospital, where their son was treated, and Scripps Health in San Diego. However, in spite of his many years tipping the speedometer, until last year Parnelli had never spent the night in a hospital.

In 2014 he underwent surgery to repair a spinal disc, followed by a three-night stay at Torrance Memorial. “I was very impressed with the new Lundquist Tower,” Parnelli says. “It’s so fresh and clean. What used to look like army barracks is now a first-class hospital.” Judy continues, “The equipment is state-of-the-art, and I love all the big windows and private rooms.”

After his stay, long-time friends and members of the Torrance Memorial Patrons program Sandy and Tom Cobb helped further guide their attention to the hospital in their own backyard. With children and grandchildren just miles away, it made sense to become Patrons of their neighborhood hospital.

“When you get to be our age, you start to think about where you may be spending a lot of your time,” Parnelli says.

For Parnelli, what also makes sense is giving back to the city where it all started. “I will always feel I am a part of Torrance. I have always claimed Torrance as my hometown.”